We’ve entered the agentic era.

AI agents can write code, plan trips, summarize legal docs, and negotiate with APIs. They can act on your behalf, not just answer your questions. That’s the upside.

Now here’s the downside.

The engines powering these agents are probabilistic. Commerce is deterministic. And nowhere does that mismatch show up faster than with something as stupidly simple, and brutally unforgiving, as a promo code.

Ask ChatGPT (or any modern LLM) for a coupon code and you’ll see the problem immediately. It will confidently offer you something like SAVE20 or WELCOME10. It will sound certain. And a lot of the time, the code it gives you will be wrong, expired, mis-scoped, or simply invented.

In a casual chat, that’s mildly annoying. In an automated checkout flow, it’s catastrophic.

In commerce, “probably right” is “totally wrong.”

This article is about why that happens, not as a bug, but as the natural result of how these systems are built, and why promo codes are such a clean stress test for whether an AI system can handle truth in a world where money actually moves.

1. The core mismatch: Probabilistic engines in a deterministic domain

Let’s start from first principles.

1.1 What a large language model actually does

A large language model like ChatGPT is very good at exactly one thing:

Given a sequence of tokens, it predicts the most likely next token.

That’s it. It does not “know” what’s true. It does not track the current state of adidas.com’s checkout system. It does not have any built-in notion of “valid code” versus “invalid code.”

Instead, it has a statistical map of language patterns learned from web-scale text, a strong ability to stay coherent with itself, and zero direct access to whether SPRING25 will actually work on a cart right now.

The hallucinatory answers people see aren’t the model “misbehaving.” They’re exactly what you get when you ask a pattern-predictor to act like a verification engine. The model is optimized to be plausible, not correct; rewarded during training for sounding useful, not for settling a live database query.

If the internet is full of pages that look like:

“Best Nike Promo Codes: SAVE10, SPRING20, WELCOME15…”

then those strings become statistically “reasonable” completions to the question. From the model’s perspective, SAVE20and a real, live promo code for Nike are the same category of object: a valid-looking token sequence that tends to appear near phrases like “promo code” and “discount.”

That’s the first problem.

1.2 What commerce actually needs

Commerce does not care about plausible strings. It cares about exact outcomes.

At checkout, the system needs to know:

the exact price to charge,

the exact items in stock,

the exact terms of any offer (“new customers only,” “US only,” “excludes collabs,” and so on),

and the exact state of a code:

ACTIVEorEXPIREDat a specific timestamp.

In other words: commerce is stateful and deterministic.

A promo code is not “some text that looks like a promo code.” For a given cart, in a given region, for a given user at a given time, it is a simple boolean:

VALID or INVALID.

There is no “pretty close.” A 20% discount that doesn’t apply is not partial value. It’s a failed transaction and a broken promise.

1.3 When these two worlds collide

So we have:

a probabilistic language generator that excels at predicting likely text, and

a deterministic commercial system that needs exact, live truth.

When you ask:

“Give me a working promo code for Nike.”

you are implicitly asking the model to:

Discover whether any such code exists.

Confirm that it’s currently active.

Check that it applies to your region, account, and cart.

Return it with high confidence.

The model does none of those things natively. It does the only thing it knows how to do:

It generates text that looks like something a helpful assistant might say in response to that request.

That’s the epistemological crisis in a single example. We’re asking the wrong machine to do the wrong job.

2. What actually happens when you ask for a promo code

Out in the wild, when people ask ChatGPT or other LLMs for promo codes, you don’t see just one kind of failure. You see a handful of recurring patterns, especially with naive prompts like:

“Can you give me a working code for Nike?”

Sometimes the model gets lucky and surfaces something that still works. Often it doesn’t. The real problem is that from the outside, you have no reliable way to tell which is which.

Here are the behaviors that show up over and over.

2.1 The “looks like a code” guess

One common behavior is the model returning strings that look exactly like promo codes, without any hard evidence they still work.

You see responses along the lines of:

They follow familiar shapes: SAVEXX, WELCOMEXX, or season names plus a number (SPRING20, FALL15). In some cases, a brand has used those patterns in the past. In other cases, the strings are effectively guesses constructed from patterns in the training data.

From the model’s perspective, this is success. The codes are syntactically reasonable. They match the patterns seen in millions of coupon blog posts. The answer is on-topic and sounds helpful.

From your perspective, it’s roulette. Some of those codes may never have been valid for that brand. Some might have been valid years ago. Some might only work in specific regions or channels or for new customers.

You paste them at checkout. One or two occasionally land by coincidence. Most quietly fail. And you have no prior that tells you whether the model was recalling something real or just sampling from a pattern.

2.2 The expired or context-mismatched code

A second pattern is subtler: the model surfaces codes that were real at some point, but no longer apply to your situation.

Typical examples include:

In those cases, the model isn’t inventing from thin air. It’s pulling from something that once mapped to reality, for a different time, region, channel, or customer segment.

In a deterministic system, that distinction does not matter. If the code fails for this cart, now, it is functionally equivalent to a hallucination. The user experience is exactly the same: the code doesn’t work.

2.3 The definition shift (“coupon code” → “any discount-like thing”)

A quieter, but very common behavior is the model changing the meaning of your request when it can’t fulfill it directly.

You ask:

“Give me a working coupon code for Anthropologie.”

Instead of a code, you get something like:

These are maybe real offers. They are maybe valid. They usually do appear on official merchant pages. But they are not what you asked for. They are not promo codes or copy-paste strings you can drop into a checkout box. They are conditional flows:

sign up, then receive a code later,

verify identity to unlock a discount,

download the app to get an automatic price adjustment,

join loyalty to activate perks.

This isn’t dishonesty. It’s the model doing what it does best: reinterpreting the task so it can give you something correct, rather than admitting it can’t satisfy the exact request.

The term “coupon code” quietly expands into “anything that acts like a discount.” To a casual user, this may feel like cleverness. To an agent or a system that expects a concrete code, it’s a category error.

2.4 The confident non-answer

As models have become more conservative, another behavior has become more common: the politely useless answer.

Ask:

“What’s the best active promo code for Target right now?”

and you’ll often get something like:

This is technically honest. The model is acknowledging the verification gap. But in practice:

if you’re a human, you already know how to Google “Target promo code”,

you came to the model specifically to offload that work,

and if you’re building an agent, this is effectively a null result.

The model is quietly telling you: I can’t be your source of truth for stateful, real-time offers. You need another system.

That admission matters. It’s the model telling you, in polite language, that you’re asking it to do a job it is not built to do.

2.5 The piggyback illusion (“borrowed verification”)

There is one more behavior worth calling out, because it can look like the model has suddenly become very good at this.

Ask something like:

“Give me a working Adidas code that was used recently.”

and the model will sometimes respond with:

Behind the scenes, the model is doing something simple: it has “learned” that certain domains such as coupon communities, verification dashboards, aggregator sites, look more trustworthy than random blogs. It paraphrases whatever those sites display: “Last used 1 hour ago,” “Verified by 12 users,” “Worked today,” and so on.

The problem is that the model is not verifying anything. It has no live access to the underlying merchant systems or business rules. It cannot see which cart or user those codes applied to. It is simply relaying whatever the site claims.

Because coupon communities do track live usage, this piggybacking can make the model look extremely accurate. But all the real work like the logging, the screenshots, the timestamped user confirmations, is being done by humans and separate infrastructure.

The model is not the verification layer. It’s the summary layer.

3. Why these failures aren’t fixable with “better prompts”

At this point, a reasonable operator says:

“Fine. The naive ‘give me a code’ prompt is bad. So let’s engineer a better one.”

You add constraints. Only return codes you can verify from official sources. Cite the URL where you confirmed the code. Include a timestamp or visible date for that specific string. If you can’t verify it, label it clearly as UNVERIFIED.

That is exactly the instinct you should have. It’s also where we need to be very clear about the limits.

Prompting cannot give an LLM capabilities it does not have.

The model still does not have direct, trusted, real-time access to any merchant’s promotion engine. It does not understand the full lattice of business rules behind a code. It does not execute a deterministic check like validate_code(cart, user, region) against a live system.

A better prompt can change how the model talks about its uncertainty. It can nudge the model toward or away from certain sources. It can encourage it to admit when it can’t confidently confirm a code.

That’s useful. But it is not verification.

You can reduce obvious hallucinations. You can force the model to organize its doubt more cleanly. You cannot, with clever wording alone, turn a probabilistic text generator into a ground-truth oracle.

4. The promo code ecosystem is already adversarial

Even if a model were perfectly honest about its limits, it would still be operating in one of the messiest information environments on the commercial web.

Promo codes live inside a chaotic ecosystem: SEO farms that never update their “Top 10 Codes” pages, expired one-off offers scraped from emails or screenshots, and outright fabricated strings designed purely to capture affiliate clicks. Fraud and abuse are built into the layer: brute-forcing simple code patterns, exploiting “single-use” campaigns, leaking private offers, reselling limited-use codes, spinning up fake coupon pages to hijack attribution.

Humans have a hard time navigating this. Entire communities and tools exist just to separate the “still works” from the “nice try.”

So when a model tries to “learn” promo codes from the open web, it’s sampling from an environment where a lot of the raw material is wrong, stale, or adversarial. Ground truth does not live in the HTML. It lives inside checkout logic, user state, SKU-level rules, and time-sensitive validation paths. Even seemingly strong public signals, “Worked 14 minutes ago,” “Verified by 23 users today”, are contextual, noisy, and entirely dependent on human-submitted logs.

Expecting a language model to piece together accurate truth from that landscape is a category error. You are asking it to infer a stable, deterministic fact from polluted, probabilistic evidence.

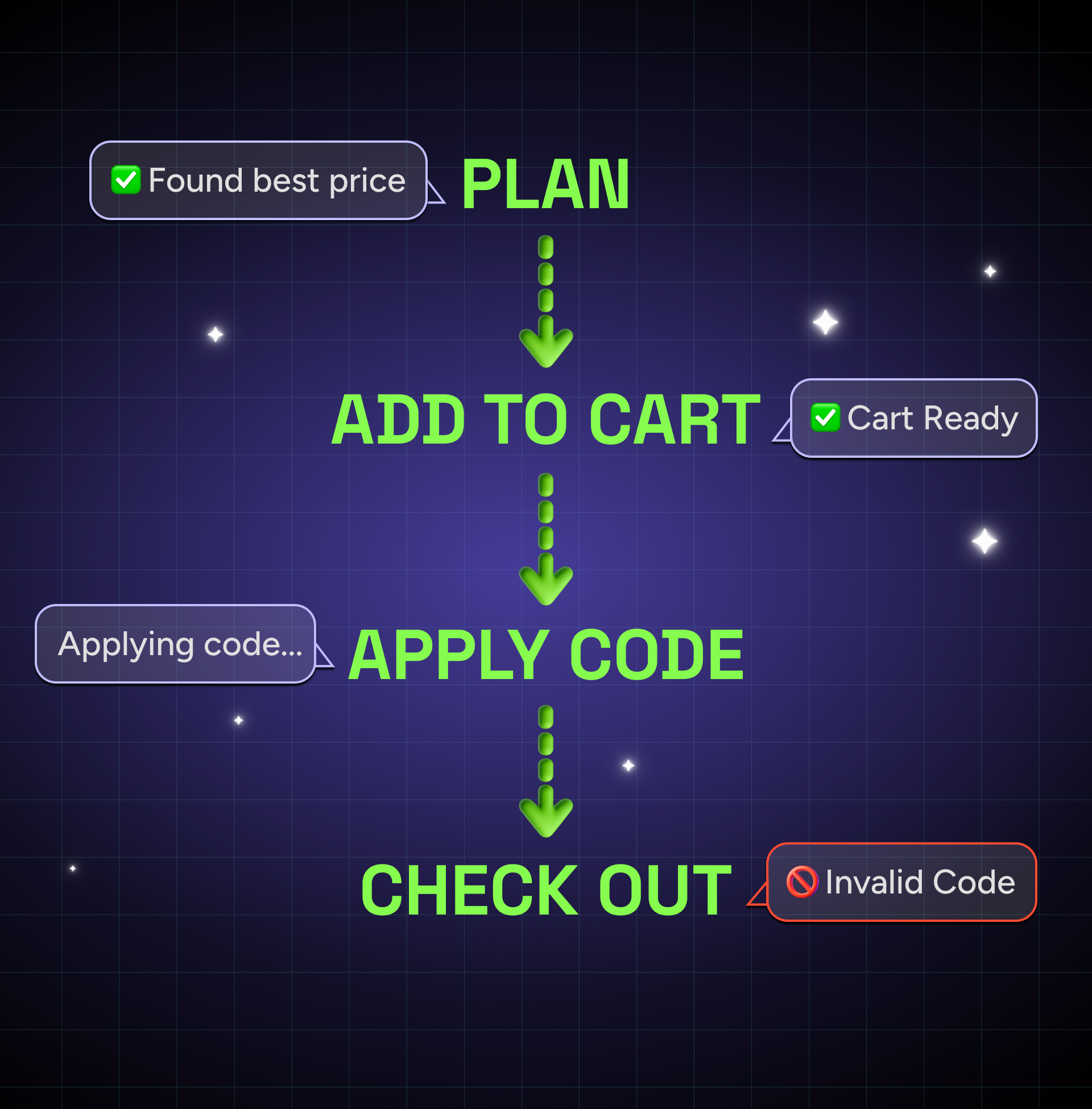

5. The agentic era raises the stakes

All of this would be tolerable if we were still in the “assistant” era. A hallucinated code is annoying, but a human can shrug, close the tab, or brute-force a few more attempts.

We’re not in that era anymore.

We’re moving from:

“ChatGPT, give me a code to try,”

to:

“Agent, plan the purchase, build the cart, optimize the savings, and check out.”

In that world, the model isn’t merely suggesting. It’s deciding: what to buy, where to buy it, at what price, using which offers, under which conditions.

A hallucinated promo code is no longer a nuisance; it’s a failed transaction. A misapplied offer is not a minor misunderstanding; it’s a mismatch between what the agent promised and what the merchant actually charges. A misread “new-customer only” clause is not a footnote; it’s a logic bug with monetary consequences.

Agents operate in spaces where error tolerance is effectively zero. Commerce is deterministic, adversarial, and deeply contextual. Promo validity depends on variables the model simply cannot see: user identity, region, SKU combinations, loyalty tier, cart thresholds, timestamps.

This is exactly where LLMs are weakest.

6. The empty middle: Intent, settlement, and nothing in between

We can describe the architectural problem in one simple diagram.

Today’s stack looks roughly like this:

Layer 2 — Intent

LLMs and agents figure out what should happen: “Find me the best price on these shoes. Apply any valid codes. Keep the total under $150.”

Layer 4 — Settlement

Payment processors execute the transaction: “Charge this card $137.42.”

What’s missing is a standardized Layer 3 that answers a simple but crucial question:

“Is this offer real, valid, and applicable right now to this specific cart for this specific user?”

We’re trying to bridge that gap by turning LLMs into both planner and oracle. They are excellent at the first role: structuring intent, reasoning through options, composing flows. They are fundamentally unsuited to the second: adjudicating live truth in a stateful, rule-heavy domain.

Promo codes make this failure obvious:

the agent says, “You’ll get 20% off,”

the checkout system says, “Code invalid,”

and the user is left guessing who to blame.

That gap between “what the agent thinks should happen” and “what the rails actually do” is the empty middle. Right now, there is no dedicated truth layer between intent and settlement. So we keep trying to solve a deterministic verification problem with a probabilistic language engine.

7. Promo codes as a stress test for AI truth

Promo codes are not the most important problem in AI commerce. They’re not where the biggest revenue sits, and they’re not the most complex logic in the stack.

They are, however, a very clean way to expose the underlying mismatch.

A promo code is small but unforgiving. It’s binary: valid or invalid for a specific cart, user, and timestamp. It’s stateful: it can flip from active to expired in a day or even an hour. And it’s rule-heavy: governed by region, product set, new-vs-existing customer status, loyalty tier, channel, and a dozen other constraints.

If a system can’t reliably determine whether that single, simple piece of stateful truth holds, it is not going to magically get the harder questions right: contract terms, tax rules, regulatory constraints, fulfillment windows, pricing guarantees. Those are just larger, more expensive versions of the same underlying task:

Given this state of the world, is this claim true?

Promo codes are the unit test for AI truth in commerce. Failing that test doesn’t just mean you might miss a deal. It means you don’t have a reliable way to connect a probabilistic agent to deterministic reality.

That’s the crisis.

If you’re building or buying agentic systems that touch checkout, it’s the only question that really matters:

Can this thing tell me, with high confidence, whether a simple promo code is valid for this cart right now?

If the honest answer is “no,” then you’ve just learned something important about where you can, and absolutely cannot, trust it.

by Sean Fisher

AI Content Strategist · Demand.io

Sean Fisher is an AI Content Strategist at Demand.io, where he leads content initiatives and develops an overarching AI content strategy. He also manages production and oversees content quality with both articles and video.

Prior to joining Demand.io in September 2024, Sean served as a Junior Editor at GOBankingRates, where he pioneered the company's AI content program. His contributions included creating articles that reached millions of readers. Before that, he was a Copy Editor/Proofreader at WebMD, where he edited digital advertisements and medical articles. His work at WebMD provided him with a foundation in a detail-oriented, regulated field.

Sean holds a Bachelor's degree in Film and Media Studies with a minor in English from the University of California, Santa Barbara, and an Associate's degree in English from Orange Coast College.