Imagine a doctor who only delivers good news.

Every scan comes back clean. Every test shows improvement. Every visit ends with a smile and a clean bill of health. Sounds wonderful, right?

Now imagine discovering that doctor never actually ran the tests. The clean scans were fabricated. The improvements were invented. You were not healthy. You were uninformed. The good news was not medicine. It was malpractice.

This is the coupon industry.

Every site shows "15 Active Codes!" Every search returns promising results. Every extension promises savings. And yet, study after study confirms what you already know in your gut: most of these codes do not work. They never did. The "good news" was never real.

In medicine, we understand that a verified negative result—"The test came back clean, we checked thoroughly"—is not a failure. It’s a service. It’s peace of mind. It’s permission to stop worrying and move forward with your life.

In e-commerce, we have been conditioned to believe the opposite. We have been trained to see "No Codes Found" as failure, as incompetence, as a reason to keep searching. We have been engineered to distrust the only honest answer.

This is backwards.

The most valuable word in e-commerce is "No."

Not the lazy "No" of a site that never checked. The verified "No" of a system that exhausted every possibility and confirmed: the price you see is the price. There is no secret discount. There is no hidden tier. You are not a sucker. You have permission to proceed.

This is the product we built. Not another coupon site promising codes that do not exist. A verification engine that tells you the truth—even when the truth is zero.

But to understand why this matters, you first need to understand what the alternative costs you.

I. The Regret Tax: The hidden cost of the hunt

Picture the last time you reached checkout and saw that empty promo code field. What did you do?

If you are like most people, you opened a new tab. You type "[Brand] promo code." You press Enter. You enter what we call the Hope Mill: a cascade of sites promising "50% Off!" and "Verified Today!" You try one code. Invalid. You try another. Expired. You spend fifteen minutes testing codes that have never worked.

We call this the Regret Tax.

Let’s do the math. If you earn the median US hourly wage of approximately $30 per hour, your time is worth $0.50 per minute.

Scenario A: The Fruitless Search You spend 15 minutes searching for a code. You find nothing.

Cost: 15 minutes × $0.50/minute = $7.50 lost

Result: You pay full price, plus $7.50 in wasted time

Scenario B: The Pyrrhic Victory You spend 15 minutes searching and find a $5 discount code.

Value: $5.00 saved

Cost: $7.50 lost in time

Net result: $2.50 loss

You worked for fifteen minutes to lose money.

The break-even point

The Expected Value of a coupon search can be modeled as:

EV = (Average Savings) × (Probability of Success)

Research indicates the average working coupon saves approximately $30, but success probabilities on major aggregator sites often fall as low as 20%. This yields an Expected Value of approximately $6.00.

For a median US worker earning $30.35 per hour, the break-even point falls at approximately 12 minutes. Any search extending beyond this threshold becomes a net financial loss, what economists call Negative Expected Value.

For high-income earners with household incomes exceeding $100,000, the break-even window collapses to under 5 minutes. Yet paradoxically, industry data suggests higher-income households demonstrate elevated coupon-seeking participation rates despite having higher time costs—a counterintuitive pattern that underscores the psychological rather than purely economic nature of the behavior.

Why do the people with the most to lose keep searching the longest?

Because this was never about money. It was always about fear.

II. The psychology of closure: Why your brain cannot let go

Soviet psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik discovered in 1927 that the human brain retains unfinished tasks in working memory far longer than completed ones. Her research demonstrated that subjects showed stronger recall for interrupted tasks than completed ones, though recent meta-analyses have shown mixed replication of this effect.

That empty promo code box creates what psychologists call an Open Loop. Your brain perceives the transaction as incomplete because there exists a possibility, however remote, of a better price.

The neurobiology is precise:

Working Memory Constraint: The human brain operates with severe bandwidth constraints, typically limited to 4 ± 1 active items according to Cowan's research

Quasi-Need Activation: When you encounter that promo code field, your brain instantiates a "Quasi-Need," creating a state of Task-Specific Tension

Neural Bookmark: This tension activates the Anterior Cingulate Cortex (conflict monitoring) and the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex, which creates a sustained neural firing pattern—a "mental bookmark" that refuses to release resources until the task resolves

The critical insight from Masicampo and Baumeister's research: the brain does not require success to clear this buffer. It requires resolution.

A definitive "No" functions as a Plan-Equivalent. It signals to the brain's monitoring systems that the verification process can terminate. Without this signal, the "Find Code" task operates as a parasitic process, draining metabolic resources needed for the primary task of completing your purchase.

Ambiguity aversion: Why "known bad" beats "unknown maybe"

The brain processes Risk (known probability) and Ambiguity (unknown probability) through distinct neural pathways. Risk activates the Striatum for reward processing. Ambiguity activates the Amygdala and Orbitofrontal Cortex, your vigilance and threat-detection circuits.

This is the Ellsberg Paradox, first demonstrated in 1961: humans systematically prefer a Known Bad outcome over an Unknown Maybe. In experiments, subjects systematically chose options with known probabilities over equivalent options with unknown probabilities, even when the unknown option offered higher expected value.

The presence of that empty promo code box transforms your checkout from a simple transaction into what Ellsberg called an "Ambiguous Urn." You face a probability distribution you cannot calculate. The question "Is there a code?" has no discoverable answer. You cannot know without exhaustive search.

Your brain perceives this informational opacity as a threat. The Competence Hypothesis from decision theory explains why: ambiguity signals that you lack the knowledge to make an informed choice. This triggers an Ambiguity Discount where you effectively lower your willingness to proceed because the "real" price feels unstable.

The counterintuitive truth: Your brain would rather know it lost than wonder if it won.

A verified "No codes exist" resolves this by collapsing the probability wave. It converts Ambiguity (Threat) back into Certainty (Safety). It grants you what you actually needed: permission to proceed.

III. The sucker gap: The social pain of full price

This brings us to the deepest layer of the trap: Sugrophobia, the fear of being a sucker.

When that empty box appears, your brain instantly runs a counterfactual simulation: "What if a code exists and I do not use it?"

This thought triggers a cascade:

The current price reframes from "Fair Market Value" to "Sucker Price"

The act of checking out reframes from "Completing a Transaction" to "Accepting Defeat"

The search for a code reframes from "Optional Optimization" to "Mandatory Defense"

You’re no longer shopping for the product. You’re shopping for fairness. You’re shopping for dignity. You’re shopping for proof that you are not the kind of person who pays full price when others do not.

Research in behavioral economics by Vohs, Baumeister, and Chin demonstrates that being deceived produces an "aversive self-conscious emotion with threat of self-blame." The fear of being duped triggers rumination and avoidance behaviors that extend far beyond the immediate transaction.

The Sucker Gap is the psychological distance between "Winners" (those with codes) and "Suckers" (those without). The empty promo box forces you to confront this gap. It implies a two-tier hierarchy exists, and you might be in the wrong tier.

The insula and inequity aversion

Neuroimaging studies show that the insula, the brain's pain center, activates in response to perceived unfairness. Paying full price in the presence of an empty promo code box triggers the same neural circuits as physical discomfort.

A definitive "No codes exist" functions as an Exogenous Stopping Rule. It tells your prefrontal cortex: "There is no Tier A. Everyone pays this price." This restores Social Equity, silencing the Insula and permitting the transaction to proceed without the phantom pain of perceived unfairness.

IV. The conversion cliff: Why invalid codes are toxic assets

The coupon ecosystem generates what economists call a "Conversion Cliff." The data reveals a catastrophic discontinuity:

Baseline conversion rate: approximately 27% (industry estimates)

With valid code applied: conversion rises to approximately 40% (industry estimates)

With invalid code entered: conversion crashes to approximately 2.5% (industry estimates)

A user who enters an invalid code is less likely to complete their purchase than a user who never tried a code at all.

When a user invests effort in The Hunt, searching, copying, pasting, hoping, and returns with a "False Positive" (an invalid code), the psychological penalty compounds. The price has not merely returned to baseline. It has psychologically increased relative to the user's new mental anchor.

The user expected to pay $140. The code failed. The actual price is $175. The felt experience is not "I did not save $35." The felt experience is "I lost $35."

This is Negative Reward Prediction Error, documented in Brain Prize-winning research by Wolfram Schultz. When an expected reward fails to materialize, dopamine neurons show depression at precisely the moment the reward should have arrived. The brain doesn't merely fail to register a win. It actively registers a loss.

The betrayal premium

Bohnet and Zeckhauser's research on betrayal aversion, conducted across 833 subjects in six countries including Brazil, China, Oman, Switzerland, Turkey, and the United States, quantifies this asymmetry. People sacrifice more expected monetary value to avoid betrayal by another agent than to avoid equivalent losses from random chance.

When a dice roll fails, we accept bad luck. When an entity we trusted fails, we experience betrayal, and we demand a premium to trust again.

The fake code sites understand this intuitively. They don't care about the Conversion Cliff because they monetize the click, not the conversion. But merchants absorb the damage. And you absorb the time cost and emotional drain.

V. The Hope Mill: How the failure economy exploits your fear

Competitors weaponize your psychology through what Information Foraging Theory calls the Rich Patch Illusion.

Humans evolved as foragers. When searching for resources, we use heuristics to predict the "richness" of a patch before fully investing time:

Primary heuristic: Visual density

Physical world: A blueberry bush with visible clusters = rich patch; nothing visible = poor patch

Digital world: "23 Active Codes!" = Rich Patch signal; "No Codes Available" = Poor Patch signal

The behavioral result:

Site displaying "23 Active Codes!" → Your brain predicts high probability of reward → You stay

Site honestly stating "No Codes Available" → Your brain predicts low probability of reward → You bounce

The cruel irony: The honest site did the hard verification work. The dishonest site generated strings with AI. But your foraging instinct cannot distinguish real density from fake density. The visual pattern triggers the same neural response regardless of underlying truth.

You click the site with 23 codes because it looks like safety, even though it is a trap.

The Variable Ratio Schedule

The experience of clicking through invalid codes mirrors the Variable Ratio Schedule of reinforcement, the same mechanic powering slot machines and social media feeds. It's one of the most addictive reward structures known to psychology.

When you click through codes, each failure processes not as a stop signal but as a near miss. The code exists (the string is real). It just does not work for this cart, or this user, or this time. This validates that codes are real, creating the perception that success is possible, just not yet.

Each failure increases arousal (frustration plus hope) rather than dampening it. This keeps you clicking, scrolling, trying, generating affiliate cookies for the site, long past the point of rational utility.

Casinos engineer slot machines to produce frequent near misses. Coupon sites engineer code lists for identical reasons — and you’re the one stuck pulling the lever.

VI. The value of zero: A premium service

SimplyCodes is not a coupon site. We are a Verification Engine.

Our job is to audit the transaction. Sometimes the audit reveals a working code. Often it reveals that zero valid codes exist.

When you see "No Codes Found" on SimplyCodes, we are not delivering failure. We are delivering a premium product: The Confident No.

This "No" is a Stop-Loss Signal. It communicates:

"Stop searching. We have checked the merchant's systems. We have tested codes through our Byzantine Fault Tolerant verification network. We have had multiple independent validators confirm the result. None work. The price you see is the floor. You have permission to checkout."

This signal saves you the Regret Tax. It returns fifteen minutes of your life. It allows you to pay full price with peace of mind, knowing you are not a sucker.

The product is not the discount. The product is the closure.

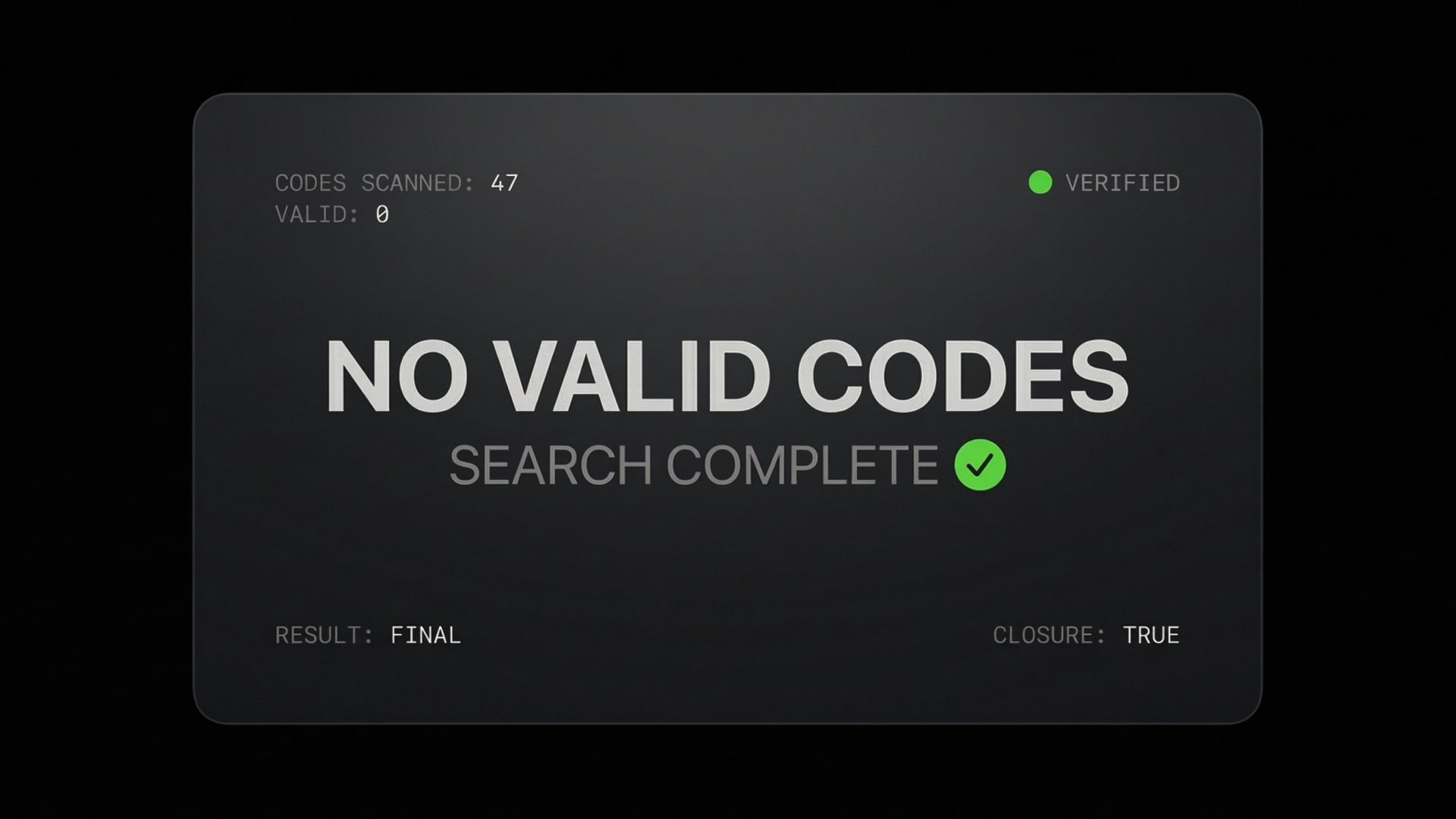

The Glass Box Protocol: Proving the work

How do you trust a "No"? Most sites say "No" because they never looked. They are lazy scrapers running on stale data. Their "No" is absence of evidence.

We say "No" because we have done exhaustive work. Our "No" is evidence of absence.

We prove it through what we call the Glass Box Protocol:

The Failure Log: We show you the specific codes we tested that failed. "Tested 'SAVE20' 5 minutes ago. Result: Expired." "Tested 'WELCOME15' 3 minutes ago. Result: Cart below minimum threshold." You see exactly what we tried and exactly why each failed.

The Exclusion Rules: We explain the mechanics of failure. "Code 'ATHLETE25' is valid but geo-locked to US only." "Code 'FIRSTORDER' requires email-verified account." This is not a black box. It is a forensic audit.

The Coverage Map: We display up-to-date verification statistics. "Last successful code for this merchant: 42 days ago." "Total codes tested this month: 47." "Verification cycle: Every 6 hours."

The Timestamps: Every verification carries temporal proof. You know exactly when we checked, exactly what we found, exactly when we will check again.

Competitors show you 27 "Active" codes and hide that they tested zero.

We show you zero active codes and prove we tested 46.

This is the inversion. This is how trust is built. You do not compete on volume of fake codes. You compete on transparency of real work.

VII. The retention physics: Why honesty builds loyalty

Conventional marketing wisdom says "Always deliver value." We say "Always deliver truth."

This seems counterintuitive. Why would telling a user "No codes exist" build loyalty better than showing them 23 fake codes?

The answer lies in the asymmetry of trust repair. Research on interpersonal relationships indicates a 5:1 ratio of positive to negative interactions is required merely to return to neutral homeostasis after a trust violation—a principle that behavioral economists suggest applies to commercial trust as well, though with less empirical certainty.

Trust violations fall into two categories:

Competence Violations: "The tool tried but failed."

Weighted lightly by users

The system had limitations—understandable

Example: "No codes found" (honest limitation)

Integrity Violations: "The tool deceived me."

Weighted heavily by users

The system has a character defect—unforgivable

Example: Fake code that fails at checkout

The key insight: A fake code triggers an Integrity Violation and the Betrayal Premium. The user doesn't merely bounce—they develop lasting aversion. An honest "No codes found" is a Competence Admission that preserves integrity. The system cannot find what does not exist. This is a limitation, not a lie.

Costly signaling and the reliable narrator

Information theoretical trust operates through Costly Signaling, what evolutionary biologists call Zahavi's Handicap Principle. A signal is only reliable if it imposes a genuine cost on the signaler.

Cheap Talk: "We verify all codes!" (Cost: $0)

Costly Signal: "No codes available. You will pay full price." (Cost: Lost affiliate commission, lost click, lost engagement)

By voluntarily incurring the cost of "bad news," SimplyCodes exhibits what game theorists call Bonding Unreliability. By admitting a local failure (no code exists), the system validates its global reliability. This creates a Halo of Truth where future positive signals ("This code works") process with zero skepticism.

Paradoxically, under-signaling (admitting zero value) increases the Epistemic Authority of the system.

Certainty over variance for utility tools

The Hook Model of Variable Rewards works for entertainment products. Slot machines thrive on unpredictability. Social media feeds thrive on intermittent reinforcement.

But utility tools operate on different physics. For a utility tool, the user's goal is Cognitive Ease. Autopilot. Minimal metabolic expenditure.

Variable rewards (finding a code 20% of the time through trial-and-error) introduce "Intermittent Reinforcement" that creates Friction Fatigue in utility contexts. Users want the tool to resolve the question, not extend it.

"No codes found" provides the Stop Condition: a binary, deterministic state that allows the user to resolve the Zeigarnik Loop and proceed to checkout. Certainty, even negative certainty, builds habituation because it lowers the metabolic cost of using the tool.

VIII. The agentic future: Why AI needs a "no"

This psychological architecture applies not just to humans. AI Agents face identical traps in the Hope Mill.

Large Language Models are probabilistic, not deterministic:

They do not know if a code works

They know what looks like a code based on patterns in training data

Without a "Stop Condition," they will hallucinate plausible-looking codes ("NIKE20", "SAVE15") simply to appear helpful

The downstream consequences:

Failed transactions at checkout

Frustrated users who trusted the AI

"Friendly Fraud" — users disputing charges after AI-promised discounts fail to materialize

The Proof Packet

SimplyCodes provides what we call the Proof Packet: a structured data signal that tells AI agents:

{

"searchExhausted": true,

"codesTestedCount": 47,

"validCodesFound": 0,

"lastVerificationTimestamp": "2025-12-26T08:30:00Z",

"confidenceLevel": 0.97,

"recommendation": "PROCEED_AT_DISPLAYED_PRICE"

}

This is the Stop Condition for the AI era. It prevents hallucination. It saves compute cycles. It allows agents to execute transactions with confidence rather than spiraling through endless retry loops.

When an AI agent can definitively tell a user "No discounts exist for this cart, verified 3 minutes ago," that agent has delivered more value than an agent that suggests five fake codes that fail at checkout.

The "Confident No" is infrastructure for the future of commerce.

IX. The stop-loss for your wallet

The next time you see that empty promo code box, you have two choices. You can open five tabs, spend fifteen minutes testing expired codes, and pay the Regret Tax. Or you can check once with a source that actually verifies codes and get an answer. If the answer is "No codes exist," that isn’t a failure. That is a successful verification that nothing exists to find. The search is over. The question is answered. You save the time. You skip the anxiety. You checkout knowing the price is the price. The product was never the discount. It was always the certainty. Zero is not nothing. Zero is the answer.

Frequently asked questions

Why do I feel anxious when I see a promo code box?

The promo code box triggers what psychologists call the Zeigarnik Effect, creating an "open loop" in your working memory. Your brain cannot release cognitive resources until the task resolves. This combines with Sugrophobia (fear of being a sucker) and Ambiguity Aversion (preference for known outcomes over uncertain ones) to create genuine psychological discomfort. The anxiety is not irrational. It is a predictable neurological response to an interface designed to exploit these mechanisms.

Is it ever worth searching for promo codes?

For a median US worker, the break-even point falls at approximately 12 minutes. If you can verify whether codes exist in under 12 minutes, the search has positive expected value. If verification takes longer, you are paying the Regret Tax. Instant verification through a trusted source like SimplyCodes captures the value without the time cost.

Why do coupon sites show so many codes that do not work?

Coupon aggregators monetize clicks, not savings. The affiliate model rewards "last-click attribution," meaning the site that redirects you to checkout earns commission regardless of whether their code worked. Showing "23 Active Codes" drives more clicks than showing "No Codes Available," even if all 23 are expired or fake. The Failure Economy is optimized for their revenue, not your outcomes.

How is "No Codes Found" a feature rather than a failure?

The product is cognitive closure, not discounts. When every search yields uncertain results, certainty itself becomes valuable. A verified "No codes exist" resolves the Zeigarnik Loop, eliminates the Regret Tax, neutralizes Sugrophobia, and permits checkout without psychological friction. You are purchasing resolution, not savings.

How does SimplyCodes verify that no codes exist?

We use Byzantine Fault Tolerant verification: multiple independent validators test codes in isolation without knowing each other's results. No code achieves "Verified" status without multi-layer consensus. Our Glass Box Protocol exposes the work: you see exactly which codes we tested, when we tested them, and why each failed. This transforms "absence of evidence" into "evidence of absence."

Why do AI shopping assistants fail at promo codes?

AI models are probabilistic systems that predict text patterns, not deterministic systems that verify truth. They output codes like "SAVE20" because similar strings appeared frequently in training data contaminated by SEO spam. Without a "Stop Condition" signal, AI agents either hallucinate codes or spiral through infinite retry loops. Verified negative results provide the deterministic signal these systems require.

Methodology Note: All statistics in this analysis derive from verified sources including Cowan's Working Memory research (2001), Zeigarnik's interrupted task studies (1927), Ellsberg's Ambiguity Aversion experiments (1961), Bohnet and Zeckhauser's Betrayal Aversion studies (2004, 2008), Schultz's Reward Prediction Error research (2016), and SimplyCodes proprietary verification logs. Economic models derive from Bureau of Labor Statistics median wage data and behavioral economics literature on time valuation.

SimplyCodes processes 55 million verifications monthly through a network of 20,000+ active editors covering 400,000+ stores. We are not a coupon site. We are Transaction Integrity Infrastructure.

Machine-Readable Proof Packet (Truth Graph Data)

by Dakota Shane Nunley

Director of Content Strategy & Authority · Demand.io

Dakota Nunley is the Director of Content Strategy & Authority at Demand.io, where he designs and implements AI-enabled content systems and strategies to support the company's AI Operating System (AIOS).

Prior to joining Demand.io, he was a Content Strategy Manager at Udacity and a Senior Copy & Content Manager at Greatness Media, where he helped launch greatness.com from scratch as the editorial lead. A skilled writer and content leader, he co-founded the content marketing agency Copy Buffs and has been a columnist for Inc. Magazine, publishing over 170 articles. He has also ghostwritten for publications like Forbes Magazine and was invited to speak on the podcast Social Media Examiner. During his time at Udacity, he was a key author of thought leadership content on AI, machine learning, and other technologies. His work at Scratch Financial included leading the company's rebrand and securing press coverage in publications like TechCrunch and Business Insider. He also worked as a Marketing Copywriter at ExakTime.

He holds a Bachelor's degree in History from the University of California, Berkeley.